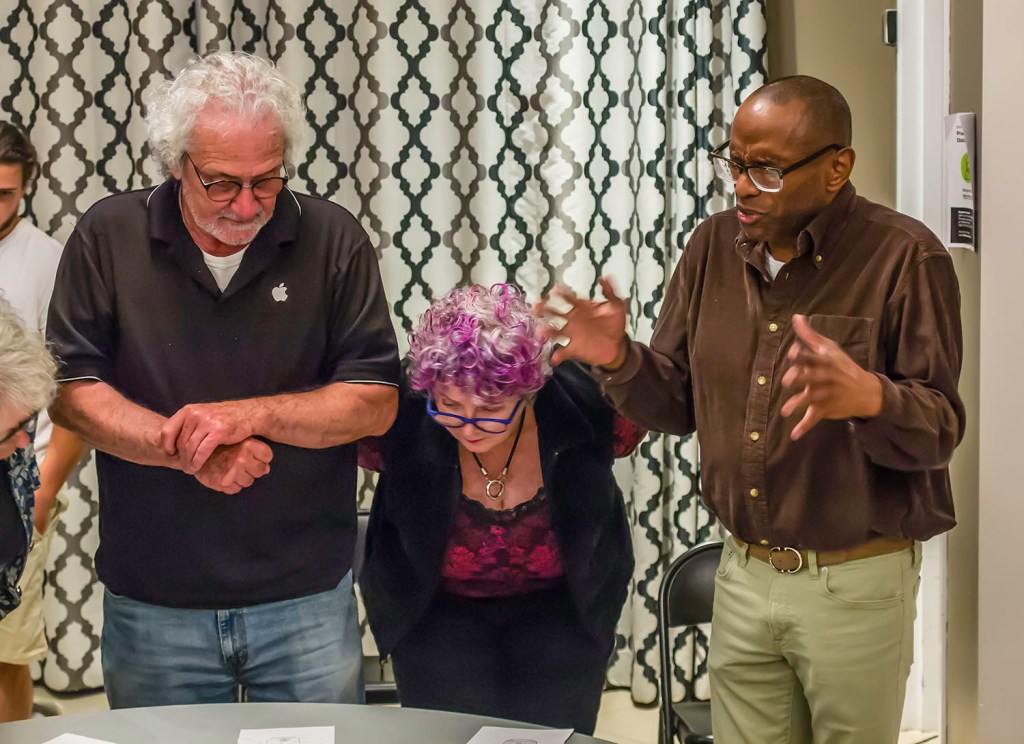

Coffee house guests met a showman with a strong voice and penetrating eye-contact. These supported the stimulating facts and anecdotes Sean George shared. He is an artist/art educator with an intriguing art history. His informed views and first-hand knowledge of the Canadian artists he discussed kept the crowd engaged.

After his illustrated talk, we had an interactive Q&A and a drawing exercise with vernissage. The audience responded with pushback, insightful comments, questions. It was a stimulating evening — grand to be talking art.

I could imagine a weekly class with Sean, generating conversations and surprised reactions. Ah, we can dream!

Below are a few photos and a brief summary of ideas we discussed.

[Photos by Milo Smith]

Pictures Come to Life by Sean George

Modern museums of art fail to tell people directly why art matters. — Alain de Botton, 2012

There is not enough consideration across Canada about the dynamic relationship between a gallery’s patrons and its art.

I am standing alone in one of the largest exhibit rooms at the Vancouver Art Gallery and trying to make ‘sense’ of the work in front of me: an enormous piece by Brian Jungen, entitled Cetology, 2002.

I move around as if stalking prey, but not quite as stealthily as the video surveillance camera that watches me. I cannot help but feel that sense of awe, amazement, and that desire to touch in order to envelop this work. I still cannot believe that something so realistically replicated is made entirely out of plastic; the same white plastic lawn chairs that inhabit yards, porches, and balconies of most Canadian homes.

How did Jungen get the idea to fashion something so vernacular and so base into a twenty-foot whale skeleton? In reality, I am asking that age old question of which came first, the chicken or the egg? Did it start with the whale? Did it start with such seemingly irrelevant ready-made chairs? What inspired such a profound cultural touchstone?

I am constructing a short talk for gallery visitors who will soon be asking me these same questions while engaging with the Jungen retrospective.

As a museum educator, I must put myself in the audience’s shoes, and help facilitate meaningful dialogue that both engages and satiates the viewer. It’s a tricky tightrope that I walk, neither making the presentation too didactic nor too ambiguous. Essentially, this concern is not one I carry alone: it is one that the museum embodies. My training suggests that all ‘good’ contemporary art should elicit questions, but my nearly 15 years of working with diverse audiences suggests otherwise.

Glancing over at the text panel I am reminded that this artwork has already been divested of its meaning, by curators, critics, and the artist himself; however, I learned early on that an artwork is not limited by the artist’s intent.

To help the discussion between the viewer and the work I use a series of entry points formally known as Project MUSE. Project MUSE is the product of a collaboration between Harvard researchers, classroom teachers, museum educators, and school principals from the US and abroad. Working for over two years, they explored the potential benefits of integrating art museum’s collections into education.

One of their findings was an educational tool called The Entry Point Approach which accommodates a range of intelligences or learning profiles. This approach has provided me with some of the necessary means of engagement.

The first entry point is aesthetic, the second narrative, the third logical/quantitative, the fourth philosophical and the fifth experiential. According to Project MUSE researchers, some of us are aesthetic learners, while some might be philosophical and others may incorporate two or more learning styles. My hermeneutic goal in looking at Cetology is to use all five entry points to bring my audience along on a journey.

My role is to be a lyrical mediator allowing the audience to fully develop their own set of questions and ideas in tandem to, or perhaps in opposition to, pre-existing ones. In presenting any existing facts or relevant ideas about the work I hope to trigger more meaningful dialogue supporting the range of intelligences that make-up an audience.

Anecdotally I have discovered that the knowledge that exists within the audience can be as diverse as the subject matter artists tackle. Bearing this in mind, I must create a safe and comfortable environment if I want the viewers to open up and share their ideas.

In a 2012 Guardian article, cultural critic Alain de Botton questions whether art should really be for its own sake. He asks if indeed museums of art are our new churches. He suggests that museums seem unable to frame their collections. And in the absence of this, they miss their opportunity to remind us why art matters and wields the power to move us in a spiritual way.

It is a mistake to believe that artists only make art for art’s sake. The many layers and discussion embedded in works from Las Meninas to Cetology is what gives art its charge, transforming the gallery from a cultural graveyard to an accessible and rich experience. The part patrons play in demystifying art is a dance between the work, and their unique subjective experience – their constant sensory filter. Which the museum must always consider.

Thanks so much for the overview. I was really sorry to miss this meeting (the days activities stretched into evening alasâ¦).

Do you have the dates set for the next meetings (coffee houses)? I would mark my calendar right away if you have them decided.

Thank you! Alison

>

LikeLike

Wednesday 23 November at 7 p.m. is the next Coffee House

LikeLike

Is it Wednesday, 22 November OR Thursday, 23 November? Thanks!

>

LikeLike

Wrong year! Monday, 20 November.

LikeLike

Thanks, Yvonne for this amazing report. What an informative evening. It was great to discuss with Sean.

LikeLike